From The Voyage of the Beagle (April 8, 1832):

Our party amounted to seven. The first stage was very interesting. The day was powerfully hot, and as we passed through the woods, everything was motionless, excepting the large and brilliant butterflies, which lazily fluttered about. The view seen when crossing the hills behind Praia Grande was most beautiful; the colours were intense, and the prevailing tint a dark blue; the sky and the calm waters of the bay vied with each other in splendour. After passing through some cultivated country, we entered a forest, which in the grandeur of all its parts could not be exceeded. We arrived by midday at Ithacaia; this small village is situated on a plain, and round the central house are the huts of the negroes. These, from their regular form and position, reminded me of the drawings of the Hottentot habitations in Southern Africa. As the moon rose early, we determined to start the same evening for our sleeping place at the Lagoa Marica. As it was growing dark we passed under one of the massive, bare, and steep hills of granite which are so common in this country. This spot is notorious from having been, for a long time, the residence of some run-away slaves, who, by cultivating a little ground near the top, contrived to eke out a subsistence. At length they were discovered, and a party of soldiers being sent, the whole were seized with the exception of one old woman, who sooner than again be led into slavery, dashed herself to pieces from the summit of the mountain. In a Roman matron this would have been called the noble love of freedom: in a poor negress it is mere brutal obstinacy. We continued riding for some hours. For the few last miles the road was intricate, and it passed through a desert waste of marshes and lagoons. The scene by the dimmed light of the moon was most desolate. A few fireflies flitted by us; and the solitary snipe, as it rose, uttered its plaintive cry. The distant and sullen roar of the sea scarcely broke the stillness of the night.

Friday, July 31, 2009

Thursday, July 30, 2009

The Shock of the New

Bliss it was in those days to be alive,

But to be young was very heaven!

Wordsworth

Richard Holmes's The Age of Wonder is a tour de force of intellectual history and biography, offering a sweeping overview of the heroic age of English Science, spanning roughly the half century from 1769 until the 1820's (Adam Kirsch's Slate review is here). Its central figures were Joseph Banks, whose infamously decadent "discovery" of Tahiti with Captain Cook gave way to later horror as many of the ship's crew succumbed to disease; William Herschel, the amateur astronomer whose epic devotion to the telescope yielded not only the discovery of Uranus, the first new planet found since ancient times, but also mind-blowing new insights into the size and age of the universe; and Humphry Davy, the prodigious chemist who experimented with nitrous oxide and identified sodium and potassium (and found time to write poetry on the side).

While some Romantic poets, such as the anti-Newtonian Blake, placed themselves in opposition to scientific efforts, others were fascinated by the new insights into nature that the age of discovery produced. These were often achieved at great risk, of course, as in the case of Mungo Park, who presumably perished while tracing the Niger river in Africa. As Holmes writes:

Then there was the young explorer Joseph Ritchie, to whom Keats gave a copy of his newly published poem Endymion, with instructions to place it in his travel pack, read it on his journey, and then 'throw it into the heart of the Sahara Desert' as a gesture of high romance. Keats received a letter from Ritchie, dated from near Cairo in December 1818. 'Endymion has arrived thus far on his way to the Desart (sic), and when you are sitting over your Christmas fire will be jogging (in all probability) on a camel's back o'er those African Sands immeasurable.' After this there was silence. Joseph Ritchie never returned.

Arguably what linked Romantic poetry and science was an exuberant optimism in the capacity of humankind for knowledge and improvement of the world:

Here Coleridge was defending the intellectual discipline of science as a force for clarity and good. He then added one of his most inspired perceptions. He thought that science, as a human activity, 'being necessarily performed with the passion of Hope, it was poetical.' Science, like poetry, was not merely 'progressive.' It directed a particular kind of moral energy and imaginative longing into the future. It enshrined the implicit belief that mankind could achieve a better, happier world. This is what Davy believed too, and 'Hope' became one of his watchwords.

Or as Holmes puts it in the final paragraph of his book:

The old, rigid debates and boundaries--science versus religion, science versus the arts, science versus traditional ethics -- are no longer enough. We should be impatient with them. We need a wider, more generous, more imaginative perspective. Above all, perhaps, we need the three things that a scientific culture can sustain: the sense of individual wonder, the power of hope, and the vivid but questing belief in a future for the globe. And that is how this book might possibly end.

I don't think it is mere pessimism to observe that science, for a long time now, has been more about anxiety and consternation than about hope and wonder. If anything, owing to overpopulation, climate change, and the perpetual risk of nuclear holocaust, there is the sense that we are living through a long a horrific hangover from an irresponsible heyday of science (or at least its willy-nilly applications). Science these days is about cleaning up our global mess, or about keeping up with the Chinese, or about buttressing our economy.

Can the Romantic spirit of science be recaptured? I wonder (so to speak). There are no new Tahitis to discover. The Romantic space program of forty years ago has yielded to the sobering realization that space is vast indeed, and humans will not personally visit much of it in the foreseeable future. Mars is a huge stretch. Jupiter? Saturn? They may as well be on the far side of the galaxy.

Biology and particularly neuroscience would seem to be the best candidates for Romantic sciences, but even in these fields, can hope be said to outweigh apprehension? For every promise of longevity and well-being there are matching bugbears of cloning, overpopulation (120-year-olds playing golf and draining Social Security), artificial intelligence, and the onset of the digital mindset. I suppose I'm biased, but perhaps psychology in its vast breadth--from the study of the neuron, to spirituality and ethics and their evolution--holds out the best hope of saving us from human, all-too-human science.

It would have been cool though to have been Humphry Davy, trying out laughing gas for the first time.

Wednesday, July 29, 2009

Rationing

As a postprandial no-show affords a little time for reflection after a hectic morning, I think about all the folks I see in this clinic, one after another until they become a blur, who are indigent, unemployed, and unable to obtain Medicaid or Medicare. This is rationing. We already ration health care, and this is how we do it, by the vicissitudes of finances and the job market.

Yes, they are seeing me, but they are very limited in their access to medications, psychotherapy, and other specialized services, such as psychological testing or substance abuse treatment. This is rationing, merely done haphazardly.

I suppose the health care mess boils down to two issues: social justice, and living within our means. Part of social justice is protecting the minority against the majority, always a challenge, by definition, in a democracy. Word is that resistance to reforming health care is growing, and Obama may fail in this as Clinton did. Why? Because most people still have health insurance and are more or less content with their coverage; they don't want to risk this in order to cover the uninsured. They enjoy seeing doctors who can bar no expense in arranging for testing and treatment. Social justice?

The perpetual refrain these days, from economists and myriad other experts, is that we can't go on this way, that is, spending a massive amount of GDP for medical results that, while spectacular in isolated cases, are merely mediocre on average. But if we are spending medically beyond our means, it appears that the public is not willing to stop yet. Perhaps we have not yet hit rock bottom; perhaps the system is rotting but not yet rotten enough. Perhaps reform is not possible until one or more of three things happens: the majority of people are actually uninsured, the majority of people are personally dissatisfied with the system, or the out-of-control medical-industrial complex really does throw the general economy into chaos.

I'm not an expert, so hopefully I'm wrong.

Yes, they are seeing me, but they are very limited in their access to medications, psychotherapy, and other specialized services, such as psychological testing or substance abuse treatment. This is rationing, merely done haphazardly.

I suppose the health care mess boils down to two issues: social justice, and living within our means. Part of social justice is protecting the minority against the majority, always a challenge, by definition, in a democracy. Word is that resistance to reforming health care is growing, and Obama may fail in this as Clinton did. Why? Because most people still have health insurance and are more or less content with their coverage; they don't want to risk this in order to cover the uninsured. They enjoy seeing doctors who can bar no expense in arranging for testing and treatment. Social justice?

The perpetual refrain these days, from economists and myriad other experts, is that we can't go on this way, that is, spending a massive amount of GDP for medical results that, while spectacular in isolated cases, are merely mediocre on average. But if we are spending medically beyond our means, it appears that the public is not willing to stop yet. Perhaps we have not yet hit rock bottom; perhaps the system is rotting but not yet rotten enough. Perhaps reform is not possible until one or more of three things happens: the majority of people are actually uninsured, the majority of people are personally dissatisfied with the system, or the out-of-control medical-industrial complex really does throw the general economy into chaos.

I'm not an expert, so hopefully I'm wrong.

Monday, July 27, 2009

Ballooning

Every now and then one comes across a book that seems written-to-order, which may also mean that one should have researched and written it oneself. So it is with me and Richard Holmes's The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science. I had enjoyed Holmes's two-volume biography of Coleridge a few years ago, and the title of his current volume made it irresistible.

I'll have more to say when I finish it, but for now I thought I'd share his account of one of the first hot air balloon rides. The first one took place in Paris in November, 1783; it was a 27-minute relatively low-altitude and haphazard drift over the rooftops (but given that it was the first ever of its kind, triumphant nonetheless). The second one occurred just ten days later, also in Paris, and was reportedly watched by several hundred thousand spectators (somehow one doesn't think about such massive assemblages prior to modern times). Here is Holmes's description:

Dr. Charles later recalled his feelings as the balloon lifted above the trees of the Tuileries and across the Seine. "Nothing will ever quite equal that moment of total hilarity that filled my whole body at the moment of take-off. I felt we were flying away from the Earth and all its troubles for ever. It was not mere delight. It was a sort of physical ecstasy. My companion Monsieur Robert murmured to me -- I'm finished with the Earth. From now on it's the sky for me! Such utter calm. Such immensity!" Benjamin Franklin, American Ambassador in Paris, watched the launch through a telescope from the window of his carriage. Afterwards he remarked: "Someone asked me -- what's the use of a balloon? I replied -- what's the use of a newborn baby?"

Two hours later they landed twenty-seven miles away at Nesle, skimming across a field and chased by a group of farm workers, "like children chasing a butterfly." Once the balloon was secured, in a moment euphoria Dr. Charles asked M. Robert to step out of the basket. Released of his weight, and with Charles alone aboard, the balloon rapidly relaunched and climbed into the sunset, reaching the astonishing height of 10,000 feet in a mere ten minutes. One thousand feet per minute: a truly formidable and terrifying ascent. Dr. Charles kept calmly observing his instruments, and making notes until his hand was too cold to grasp the pen. "I was the first man ever to see the sun set twice in the same day. The cold was intense and dry, but supportable. I had acute pain in my right ear and jaw. But I examined all my sensations calmly. I could hear myself living, so to speak."

He began gently to release the hydrogen gas-valve. Within thirty-five minutes he was safely back on terra firma--a term that took on new meaning--alighting a mere three miles from his first landing point. His ascent had been almost vertical. It was the first solo flight in history. "Never has a man felt so solitary, so sublime,--and so utterly terrified." Dr. Charles never flew again.

For sheer novelty and adventure, did the moon landing have anything on this?

I'll have more to say when I finish it, but for now I thought I'd share his account of one of the first hot air balloon rides. The first one took place in Paris in November, 1783; it was a 27-minute relatively low-altitude and haphazard drift over the rooftops (but given that it was the first ever of its kind, triumphant nonetheless). The second one occurred just ten days later, also in Paris, and was reportedly watched by several hundred thousand spectators (somehow one doesn't think about such massive assemblages prior to modern times). Here is Holmes's description:

Dr. Charles later recalled his feelings as the balloon lifted above the trees of the Tuileries and across the Seine. "Nothing will ever quite equal that moment of total hilarity that filled my whole body at the moment of take-off. I felt we were flying away from the Earth and all its troubles for ever. It was not mere delight. It was a sort of physical ecstasy. My companion Monsieur Robert murmured to me -- I'm finished with the Earth. From now on it's the sky for me! Such utter calm. Such immensity!" Benjamin Franklin, American Ambassador in Paris, watched the launch through a telescope from the window of his carriage. Afterwards he remarked: "Someone asked me -- what's the use of a balloon? I replied -- what's the use of a newborn baby?"

Two hours later they landed twenty-seven miles away at Nesle, skimming across a field and chased by a group of farm workers, "like children chasing a butterfly." Once the balloon was secured, in a moment euphoria Dr. Charles asked M. Robert to step out of the basket. Released of his weight, and with Charles alone aboard, the balloon rapidly relaunched and climbed into the sunset, reaching the astonishing height of 10,000 feet in a mere ten minutes. One thousand feet per minute: a truly formidable and terrifying ascent. Dr. Charles kept calmly observing his instruments, and making notes until his hand was too cold to grasp the pen. "I was the first man ever to see the sun set twice in the same day. The cold was intense and dry, but supportable. I had acute pain in my right ear and jaw. But I examined all my sensations calmly. I could hear myself living, so to speak."

He began gently to release the hydrogen gas-valve. Within thirty-five minutes he was safely back on terra firma--a term that took on new meaning--alighting a mere three miles from his first landing point. His ascent had been almost vertical. It was the first solo flight in history. "Never has a man felt so solitary, so sublime,--and so utterly terrified." Dr. Charles never flew again.

For sheer novelty and adventure, did the moon landing have anything on this?

Saturday, July 25, 2009

Art and Craft

"In My Craft or Sullen Art"

Dylan Thomas

When I read Denis Dutton's The Art Instinct a while back, I was struck by his persuasive distinction between craft and art. A craft is an act of making in which the end product is known ahead of time, and one can reliably follow a list of instructions in order to arrive at that product. In the case of artistic making, while the end product is imagined more or less specifically ahead of time, the process of making is itself an act of discovery, in which no unambiguous list of instructions, but rather serendipity and unconscious insights may play a major role, such that the end product may turn out quite different from initially conceived. Like most distinctions, this one is not absolute, but it may nonetheless be useful.

It occurs to me that happiness--or the more ambitious notion of the well-lived life--has elements of both craft and art. Like anyone in the mental health field, I am asked occasionally for recommendations of "self-help" books, but I have never had much confidence in the genre. If one walks down any self-help aisle in a bookstore one encounters the same dozen or so unobjectionable but generic recommendations, packaged and re-packaged in myriad ways. What is desired, it would seem, is a list of instructions for the craft of happiness. Follow these rules and you will be happy.

"The Happiness Project," a blog by Gretchen Rubin, is a relatively endearing instance of the self-help genre, largely because of her self-deprecating, no-nonsense style. Her ideas are straightforward and commonsensical. Inasmuch as happiness can be a craft, this is as succinct and reasonable an instruction book as any. Indeed, she has her list of "twelve commandments" with inoffensive suggestions such as: be yourself, be kind, don't keep score, try new things, live generously.

There are a number of basic behaviors that, as not only wisdom literature but also abundant research shows, boost happiness (or at least are correlated with greater well-being; the direction of causation is harder to demonstrate). Eat a balanced diet. Don't smoke or use drugs. Drink alcohol in moderation if at all. Get adequate sleep. Obtain a good education. Maintain a network of supportive relationships. Do measures like these suffice to produce happiness?

It may be that following such rules produce happiness in at least a minimal, craft-like fashion, but they do no better than create the possibility for a higher ideal of happiness as a well-lived life. Similarly, suppose that one wants to fashion not only a functional table, but a table that will be an object of great ingenuity, beauty, and aesthetic distinction. To do this, one must first of all master the basic aspects of woodworking; the table as work of art must first of all have four sturdy legs, an even surface, and weight-bearing capacity. There are clear instructions for the latter, but none for the would-be artist of the table.

The self-help genre, exemplified by Rubin's "The Happiness Project," is very much like an instruction booklet for making tables. It seeks to remove frank impediments to happiness in the same way that the craft booklet seeks to establish a board resting on four legs. But beyond that, happiness, like life, is very much a matter of contingency and fine judgment. This is shown by the fact that some of Rubin's suggestions, as she acknowledges, are contradictory and paradoxical. Accept yourself as you contingently are, but try to improve yourself where possible. It is important to have an independent identity and not to rely on others for happiness, yet it is demonstrably true that healthy relationships foster happiness. How can all of this be true?

Perhaps there is a recipe for the well-lived life, but the problem is that it is far too abstract. There are rules, but as to the question of when and where to apply a particular one, the answer is always "it depends." Few of us are artists in any conventional sense, but arguably we are all condemned to be artists of the self and of the life; some of us come off quite well, while some of us botch the job. And this need not be a matter of pride or shame; Salieri can't be blamed for not being Mozart, and Mozart can't claim complete credit, as many factors beyond his will went into the making of Mozart.

We talk of psychotherapy, or of happiness, as if it is a unitary thing, but arguably there are as many kinds of both as there are people. Some psychotherapy is basic training for the making of functional tables. Some people want guidance in refinishing a table, or perhaps they think so, until it turns out that it is wobbly, and it turns out they need to go back to basic instructions. Some people have a beautiful table and want a mentor to help them to make it still better, or to use it to its best advantage. Some have inherited a table that seems burdensome in its ugliness, or its perfection. And it is not given to some people to make tables--perhaps they should make something else.

Why can't some people seem to get their tables made? They may lack the strength or coordination, both by inheritance or habituation. They may have had an accident that limited them forever. They may lack self-confidence or initiative, and may want someone else to make their table for them. After they build one, someone may come along and destroy it. Fatally, some may despair of the point of making tables at all.

The analogy has probably grown tiresome, but it helps me to understand some of my own ambivalence over self-help approaches. Medication I suppose may provide the fundamental conditions for building a table: basic supplies, and strength and steadiness of hand--as a psychiatrist I often find myself as a purveyor, then, of power tools as it were. The kind of psychotherapy that interests me entails looking at internal resistances to the building of tables, or debates about what type of table should be built, or optimizing a table already built. But for cognitive-behavioral therapy, which is a table-making booklet in twelve easy steps, there is the self-help aisle.

Thursday, July 23, 2009

The Sunlight on the Garden

The sunlight on the garden

Hardens and grows cold,

We cannot cage the minute

Within its nets of gold,

When all is told

We cannot beg for pardon.

Our freedom as free lances

Advances towards its end;

The earth compels, upon it

Sonnets and birds descend;

And soon, my friend,

We shall have no time for dances.

The sky was good for flying

Defying the church bells

And every evil iron

Siren and what it tells:

The earth compels,

We are dying, Egypt, dying

And not expecting pardon,

Hardened in heart anew,

But glad to have sat under

Thunder and rain with you,

And grateful too

For sunlight on the garden.

Louis MacNeice

Hardens and grows cold,

We cannot cage the minute

Within its nets of gold,

When all is told

We cannot beg for pardon.

Our freedom as free lances

Advances towards its end;

The earth compels, upon it

Sonnets and birds descend;

And soon, my friend,

We shall have no time for dances.

The sky was good for flying

Defying the church bells

And every evil iron

Siren and what it tells:

The earth compels,

We are dying, Egypt, dying

And not expecting pardon,

Hardened in heart anew,

But glad to have sat under

Thunder and rain with you,

And grateful too

For sunlight on the garden.

Louis MacNeice

Wednesday, July 22, 2009

One-Way Ticket to Paradise?

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star'd at the Pacific--and all his men

Look'd at each other with a wild surmise

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

Keats

The 40th anniversary of Apollo 11 provoked widespread hand-wringing and bafflement over the failure of the space program to further manned space exploration, most obviously of Mars. So I was struck by a piece in Universe Today that related a former NASA engineer's proposal to facilitate the manned exploration of the red planet with a one-way, one-person mission.

The problem with going to Mars, as with (wo)manned space travel in general, entails risk and cost. Compared to past ages of exploration, when folks routinely set sail, disappeared into the jungle, or ventured to the poles at tremendous risk and often never to return, our society, perhaps due to instant media ubiquity of any disaster, arguably is more risk-averse, perhaps too much so to send astronauts on a highly perilous Martian adventure. Personally undertaken risk is one thing, but officially (or even globally) sanctioned risk is another. If the first group of astronauts were to die, pathetically and millions of miles out, but under anguished global scrutiny, the symbolic tragedy would be crushing.

The moon is some 250,000 miles from earth; Mars is some 36 million miles away at its closest, and the trip would take roughly 9 months one-way. That implies a lot of snacks and other materials to pack for multiple astronauts making a round-trip journey. And having to take off from Mars to return to Earth is a daunting challenge.

So the argument for a one-way, one-person mission is that of a much leaner and cheaper undertaking. The article mentions blandly that it could be seen as a suicide mission; well, of course it's a suicide mission in a way, but perhaps only in the way that life itself is a suicide mission, that is, no one gets out of here alive as the adage goes. But could one say that to be the first human being to walk on Mars would provide one extraordinary person with a life far more memorable and meaningful than many longer ones?

There is something atavistic about the notion; the lone traveller would be as a willing sacrifice, not to a god or dragon, but to humanity's desperate need to know and to explore at all cost. Would anyone volunteer? The question more properly is: how many thousands or even millions would volunteer? The line of daredevils, fanatics, depressives, and misfits would stretch for miles. Oh to be the shrink to decide who was most fit to go!

As the piece suggests, this speculative astronaut (although even in this post-feminist age, could it be other than a man?) would enter a strange realm of globally scrutinized solitude. He would become at once the most isolated human being in history in physical terms, and yet emotionally and cybernetically he would be crowded and enveloped by the wonder and curiosity of six billion.

Neil Armstrong has famously become a recluse, and so far as I saw took minimal part in the anniversary festivities. What does it do to a man to be the first to step on another world? On Mars one would see Earth not as a massive sphere, cloud-brushed and cerulean, rising gloriously over a bleak horizon, but as a faintly bluish dot wandering amid the stars. One would feel truly at the end of space and time. No way out.

What would the end point be? To allow oneself to succumb to dehydration and delirium, to see what waking dreams may come beneath the dim Martian sun? To scale Olympus Mons, the highest volcano in the solar system, and throw oneself melodramatically off? Or perhaps to find some cozy cave, where the frigid, airless, and lifeless Martian environment may preserve a human artifact, to be discovered by other, more fortunate explorers thousands of years in the future? A bit morbid, a bit freakish for NASA I fear; definitely not suited for prime time (but all the more interesting for that).

Tuesday, July 21, 2009

Heavenly Bodies

As I was reflecting on the Earth-sized impact site just found on Jupiter, and the impending solar eclipse, this D. H. Lawrence poem came to mind:

Southern Night

Come up, thou red thing.

Come up, and be called a moon.

The mosquitoes are biting to-night

Like memories.

Memories, northern memories,

Bitter-stinging white world that bore us

Subsiding into this night.

Call it moonrise

This red anathema?

Rise, thou red thing,

Unfold slowly upwards, blood-dark;

Burst the night's membrane of tranquil stars

Finally.

Maculate

The red Macula.

Monday, July 20, 2009

This is Your Brain on Drugs

The debate over marijuana continues apace, with two new New York Times articles (here and here) discussing the increased potency of contemporary cannabis and its implications for addiction and speculative legalization. (Tellingly, these articles were in the "Fashion and Style" and "Opinion" sections, not "Health" or "Science").

I express no clinical or other opinion here about the issue, but merely report what I've observed about patient reports of marijuana in 15 years of general psychiatric practice, both inpatient and outpatient (I do not subspecialize in substance abuse issues, but the matter of substances comes up frequently in general practice).

In working with addicts one expects to encounter denial or, at best, ambivalence about the impact of substance use, but nonetheless I have met numerous patients over the years who fully acknowledge, whether spontaneously or when pressed, that their use of alcohol, cocaine, opioids, or amphetamine is problematic or destructive. However, I can probably count on the fingers of one hand the number of people I've worked with in 15 years who could be brought to see their marijuana use as dysfunctional (I mean, to really and painfully see it, not to vaguely humor me in considering the notion). To be sure, many patients suffer consequences from the drug's illegality, but that doesn't really count in assessing its dangerousness. Tobacco smokers on average are far more alarmed about their habit than pot smokers.

Again, I mention this not to condone its use, whether personally or professionally, but to wonder at what a strange drug it is. Its detrimental effects, such as they are, must therefore be insidious in the extreme, and not such as to disrupt life on a day-to-day basis. Indeed, more than with any other drug (even alcohol and tobacco), marijuana users tend to justify their habit as being calming and therapeutic (although some report that it makes them, if anything, more anxious). Many see it as a kind of alternative medicine, not so much different from taking St. John's Wort or other herbal preparations. If marijuana deprives its users of what would otherwise be a better pot-free life, it does so in such a way that they are unable to see what they're missing. To be sure, all addictive substances do this to a degree, but pot seems to do it more than most.

Laura Miller at Salon reviews a book by Ryan Grim called This is Your Country on Drugs: A Secret History of Getting High in America. I haven't read the book, but the article suggests that a central theme is the ubiquity of mind-altering substances throughout history and various cultures. This suggests that a central characteristic of consciousness is a desperate need to be other than it is; many accomplish this by means of other human beings, the arts, or God, but for many, directly biological self-management is too tempting to avoid altogether. Substances can and should be managed and regulated, but any attempt to suppress their use altogether may have unintended consequences, as the review suggests.

Saturday, July 18, 2009

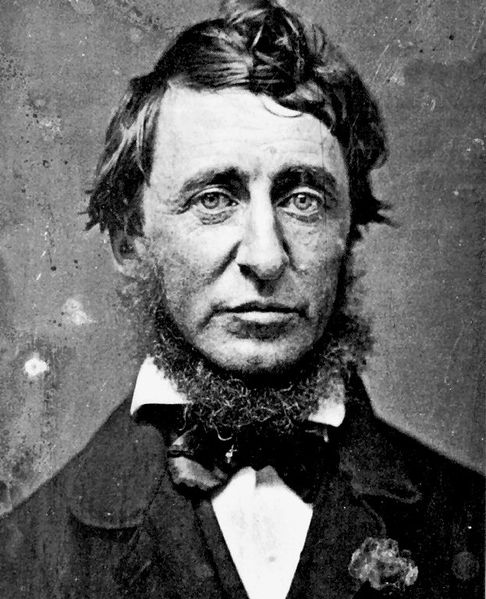

"That Terrible Thoreau"

I always think about Thoreau more this time of year. It was in summer when I first read Walden some twenty years ago, and in this prodigal season the notion of giving oneself unto the wilderness seems at least not entirely mad.

Fellow blogger Retriever offers some thoughts about Thoreau this morning, and like most she is ambivalent about him. But what troubles her is that he seems "self-conscious," "full of himself," even "adolescent." Maybe, but if so, any rebel or even any prophet is these things as well.

I have always felt some affinity with Thoreau, but have also found him remote and strange; he is that perplexing quantity, the unrepresentative guide. He was extremely focused and intense, but also narrow. He saw many values in life as commonly lived to be unnecessary and wasteful, but it is easy to feel this way when one experiences no need for such things. He felt no need for (or at least disavowed any need for), among countless other things, Beethoven, wine, sex, and children. He had no patience--no experience even perhaps--of the frailties and self-indulgencies that afflict the average Homo sapiens. He would have been the personal trainer from hell.

Indeed it is as secular prophet that I tend to see Thoreau. He had his eyes not on heaven of course, but upon a different world, a radically different kind of life, than most people in the history of humanity have been content to lead. A great redwood towering alone amid a desolate but intricately beautiful plain, he offered an ideal; one keeps the tree perpetually in mind, and turns around to gaze at it now and then while going about one's business, but few go to live there. He was too pure for us, too scrupulous and uncompromising, that asymptote we can never quite reach. He would not grant that there is not just one great Good in life, but a diversity of competing goods, and that is what makes the business of living so fiendishly difficult. Truth itself has rival goods.

Even Emerson, who travelled far indeed in the realms of thought, found Thoreau to be a distant destination. In his elegy for Thoreau, he wrote:

Thoreau was sincerity itself, and might fortify the convictions of prophets in the ethical laws by his holy living. It was an affirmative experience which refused to be set aside. A truth-speaker he, capable of the most deep and strict conversation; a physician to the wounds of any soul; a friend, knowing not only the secret of friendship, but almost worshipped by those few persons who resorted to him as their confessor and prophet, and knew the deep value of his mind and great heart. He thought that without religion or devotion of some kind nothing great was ever accomplished: and he thought that the bigoted sectarian had better bear this in mind.

His virtues, of course, sometimes ran into extremes. It was easy to trace to the inexorable demand on all for exact truth that austerity which made this willing hermit more solitary even than he wished. Himself of a perfect probity, he required not less of others. He had a disgust at crime, and no worldly success would cover it. He detected paltering as readily in dignified and prosperous persons as in beggars, and with equal scorn. Such dangerous frankness was in his dealing that his admirers called him "that terrible Thoreau," as if he spoke when silent, and was still present when he had departed. I think the severity of his ideal interfered to deprive him of a healthy sufficiency of human society.

A great tree, indeed. Emerson also quoted: "I love Henry," said one of his friends, "but I cannot like him; and as for taking his arm, I should as soon think of taking the arm of an elm-tree."

Flies in the Ointment

A. In this week's New York Times Peter Singer (a philosopher who, like gadfly Socrates I suppose, makes it his practice to publicly point out inconvenient truths, like the contingency of world poverty and the role of animals in our food supply), makes the incontrovertible case for rationing health care. The sad thing (for our cherished vision of ourselves as rational creatures) is that this is still a case that has to be made.

Health care is an expensive commodity, particularly with respect to end-of-life care and the cutting-edge or experimental treatment of severe conditions. I'm no economist, but I think most would agree that resources, ultimately, are finite. How could we think that health care could not be rationed? The question is merely how it can be most justly rationed. Isn't every other commodity rationed? Is everyone guaranteed an Ivy League education, or a private jet? The point is not that life is not precious, but that given limited resources it cannot possibly be infinitely precious (in dollar terms). If it were, we would be spending 100% of GDP on health care.

(Addendum: Jacob Weisberg has a pertinent article in Slate that looks at the health care system, and prospects for reform, as reflections of American culture and values).

B. Somebody in psychiatry (besides me) has some sense. Allen Frances, M.D. the chair of the Task Force that developed the DSM-IV, published in 1994, has written this scathing criticism of the process under way to produce the DSM-V by 2012. He points out the generally haphazard, secretive, and underfunded nature of the endeavor, but his two bigger points are these:

1. Practical knowledge in psychiatry has not increased sufficiently in the past 15 years to justify radical revisions of diagnostic criteria. Research in neuroscience has generated oceans of theoretical information, but none of this yet alters what a psychiatrist can practically do for a patient in the office. So wholesale diagnostic changes amount to what Frances aptly likens to merely rearranging the furniture.

2. The addition of milder, "subthreshold" conditions threatens to greatly expand the prevalence of "mental disorders," which will in turn generate numerous "false positives" and play into the hands of both pharmaceutical companies eager for new "patients" as well as those eager to criticize psychiatry's imperialistic tendencies. There is already plenty of controversy over exploding diagnoses such as bipolar disorder and ADHD; to codify a wider purview for these in DSM-IV would merely fan the flames.

Psychiatry may be well-intentioned, but it is forever trying to advance farther than its secure knowledge base justifies, and at times it seems like one colossal hammer that is hallucinating nails wherever it looks.

As full disclosure and on a personal note, I would add that soon after I was accepted for my psychiatry residency at Duke in 1995, I received in the mail a warm-off-the-press edition of the DSM-IV signed by none other than Allen Frances, who was chairman at that time. He would agree (and has often volunteered) that the DSM-IV is a flawed instrument, as it would have to be; we just haven't advanced enough yet to radically improve upon it.

Health care is an expensive commodity, particularly with respect to end-of-life care and the cutting-edge or experimental treatment of severe conditions. I'm no economist, but I think most would agree that resources, ultimately, are finite. How could we think that health care could not be rationed? The question is merely how it can be most justly rationed. Isn't every other commodity rationed? Is everyone guaranteed an Ivy League education, or a private jet? The point is not that life is not precious, but that given limited resources it cannot possibly be infinitely precious (in dollar terms). If it were, we would be spending 100% of GDP on health care.

(Addendum: Jacob Weisberg has a pertinent article in Slate that looks at the health care system, and prospects for reform, as reflections of American culture and values).

B. Somebody in psychiatry (besides me) has some sense. Allen Frances, M.D. the chair of the Task Force that developed the DSM-IV, published in 1994, has written this scathing criticism of the process under way to produce the DSM-V by 2012. He points out the generally haphazard, secretive, and underfunded nature of the endeavor, but his two bigger points are these:

1. Practical knowledge in psychiatry has not increased sufficiently in the past 15 years to justify radical revisions of diagnostic criteria. Research in neuroscience has generated oceans of theoretical information, but none of this yet alters what a psychiatrist can practically do for a patient in the office. So wholesale diagnostic changes amount to what Frances aptly likens to merely rearranging the furniture.

2. The addition of milder, "subthreshold" conditions threatens to greatly expand the prevalence of "mental disorders," which will in turn generate numerous "false positives" and play into the hands of both pharmaceutical companies eager for new "patients" as well as those eager to criticize psychiatry's imperialistic tendencies. There is already plenty of controversy over exploding diagnoses such as bipolar disorder and ADHD; to codify a wider purview for these in DSM-IV would merely fan the flames.

Psychiatry may be well-intentioned, but it is forever trying to advance farther than its secure knowledge base justifies, and at times it seems like one colossal hammer that is hallucinating nails wherever it looks.

As full disclosure and on a personal note, I would add that soon after I was accepted for my psychiatry residency at Duke in 1995, I received in the mail a warm-off-the-press edition of the DSM-IV signed by none other than Allen Frances, who was chairman at that time. He would agree (and has often volunteered) that the DSM-IV is a flawed instrument, as it would have to be; we just haven't advanced enough yet to radically improve upon it.

Friday, July 17, 2009

Moving Day

This blog(ger) is officially moving today to its successor site Blue to Blue (http://www.bluetoblue.org/). As I've said, the content will be similar, so if you've stayed with me so far, I hope you'll come along.

To those kind bloggers who have included Ars Psychiatrica in your blogrolls, I hope you will kindly replace it in your lists with its sequel, and I regret your trouble in doing so. Ars Psychiatrica in its current state will remain online, but future posts will appear on Blue to Blue.

Thanks for reading.

To those kind bloggers who have included Ars Psychiatrica in your blogrolls, I hope you will kindly replace it in your lists with its sequel, and I regret your trouble in doing so. Ars Psychiatrica in its current state will remain online, but future posts will appear on Blue to Blue.

Thanks for reading.

Let's Try This Again

Picking up where Ars Psychiatrica left off (trailed off?), Blue to Blue will contain observations--and sometimes flights of fancy--related to psychology and the arts (both broadly construed). As compared to its prequel, you may notice three minor modifications:

1. A more minimalist look. I'm sure I'll add a few more touches over time.

2. I am giving Twitter a try; as I enjoy both prolific Web links and pithy, gnomic utterances (both my own and others'), it may offer more than merely a waste of time (Twitter-fritter). If you will sign up to follow, I will spare you the burden of Too Much Information (about my daily doings, that is, not to mention...unmentionables).

3. I have reverted to quasi-anonymity. No particular problem arose from my name attached to the other blog, and no blogger enjoys absolute anonymity anyway, but I find that I feel a bit freer with the added degree of discretion.

Thanks for reading.

1. A more minimalist look. I'm sure I'll add a few more touches over time.

2. I am giving Twitter a try; as I enjoy both prolific Web links and pithy, gnomic utterances (both my own and others'), it may offer more than merely a waste of time (Twitter-fritter). If you will sign up to follow, I will spare you the burden of Too Much Information (about my daily doings, that is, not to mention...unmentionables).

3. I have reverted to quasi-anonymity. No particular problem arose from my name attached to the other blog, and no blogger enjoys absolute anonymity anyway, but I find that I feel a bit freer with the added degree of discretion.

Thanks for reading.

Thursday, July 16, 2009

Fortyish Food for Thought

A section of William Butler Yeats's "Vacillation:"

Get all the gold and silver that you can,

Satisfy ambition, or animate

The trivial days and ram them with the sun,

And yet upon these maxims meditate:

All women dote upon an idle man

Although their children need a rich estate;

No man has ever lived that had enough

Of children's gratitude or woman's love.

No longer in Lethean foliage caught

Begin the preparation for your death

And from the fortieth winter by that thought

Test every work of intellect or faith

And everything that your own hands have wrought,

And call those works extravagance of breath

That are not suited for such men as come

Proud, open-eyed and laughing to the tomb.

The full poem is here.

Wednesday, July 15, 2009

From Cradle to Grave

Winslow Homer, Northeaster

"Life is a series of hellos and goodbyes,

I'm afraid it's time for goodbye again."

Billy Joel, "Say Goodbye to Hollywood" (for Anonymous)

A highfalutin way of saying the same thing is Walt Whitman's prodigious "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking," the first and last sections of which follow:

Out of the cradle endlessly rocking,

Out of the mocking-bird's throat, the musical shuttle,

Out of the Ninth-month midnight,

Over the sterile sands and the fields beyond, where the child

leaving his bed wander'd alone, bareheaded, barefoot,

Down from the shower'd halo,

Up from the mystic play of shadows twining and twisting as

if they were alive,

Out from the patches of briers and blackberries,

From the memories of the bird that chanted to me,

From your memories sad brother, from the fitful risings and

fallings I heard,

From under that yellow half-moon late-risen and swollen as if

with tears,

From those beginning notes of yearning and love there in the

mist,

From the thousand responses of my heart never to cease,

From the myriad thence-arous'd words,

From the word stronger and more delicious than any,

From such as now they start the scene revisiting,

As a flock, twittering, rising, or overhead passing,

Borne hither, ere all eludes me, hurriedly,

A man, yet by these tears a little boy again,

Throwing myself on the sand, confronting the waves,

I, chanter of pains and joys, uniter of here and hereafter,

Taking all hints to use them, but swiftly leaping beyond

them,

A reminiscence sing.

------

Whereto answering, the sea,

Delaying not, hurrying not,

Whisper'd me through the night, and very plainly before

daybreak,

Lisp'd to me the low and delicious word death,

And again death, death, death, death,

Hissing melodious, neither like the bird nor like my arous'd

child's heart,

But edging near as privately for me rustling at my feet,

Creeping thence steadily up to my ears and laving me softly

all over,

Death, death, death, death, death.

Which I do not forget,

But fuse the song of my dusky demon and brother,

That he sang to me in the moonlight on Paumanok's gray

beach,

With the thousand responsive songs at random,

My own songs awaked from that hour,

And with them the key, the word up from the waves,

The word of the sweetest song and all songs,

That strong and delicious word which, creeping to my feet,

(Or like some old crone rocking the cradle, swathed in sweet

garments, bending aside,)

The sea whisper'd me.

The full poem is here.

Tuesday, July 14, 2009

Bruno: The Definitive (Thumbnail) Review

I don't make it to the movies very often (I feel fairly sure the Blue Flower doesn't grow there), so when I do, it's worth a post. I enjoyed Bruno more than I expected to (the umlaut is there, it's just really small). What I disliked about Borat was not the ridicule of those who richly deserved it (Pamela Anderson; the rabidly xenophobic rodeo crowd), but the humiliation of a number of well-intentioned but typically (American) average folks who committed the crime of being insularly ignorant about "furriners."

Bruno manages to offend just about everyone, but the object of satire per se is the absurdly hubristic figure of Bruno himself, and what is satirized is not so much homosexuality or its practices as the universal target of satire: self-important buffoonery. Sure, it pokes fun at both homosexuals and homophobes, but it does not impale (so to speak). The raunchiness certainly is a bit much (as I'm sure it was intended to be), but it doesn't negate the hilarity of Bruno lurching, Kramer-like, head first into one metaphorical wall after another.

The opening minutes, in which Bruno throws a ripe-for-disruption fashion show into an uproar by wearing an all-velcro suit (and having a disastrous encounter with a curtain), are worth admission in themselves. I also particularly enjoyed the Paula Abdul segment (because of what she sits on) as well as the tableau of Bruno, ludicrously attired in African garb, removing from an airport baggage carousel a large tusk, an elephant foot, and a box marked "fragile" and containing a black baby. Everything is over-the-top, but that is Sacha Baron Cohen's shtick. The Ron Paul piece wasn't funny (he was one of the few unsuspected targets who acted with unsanctimonious dignity) and should have been cut, but overall Bruno wisely clocks in at (I'm guessing) 90 minutes or so. In an age when even good movies are too long (everything is getting quicker--except movies), this is a triumph in itself.

Bruno is not for the sexually squeamish, and its gay theme is no instance of social activism, but when it is funny, it is very funny indeed.

Bruno manages to offend just about everyone, but the object of satire per se is the absurdly hubristic figure of Bruno himself, and what is satirized is not so much homosexuality or its practices as the universal target of satire: self-important buffoonery. Sure, it pokes fun at both homosexuals and homophobes, but it does not impale (so to speak). The raunchiness certainly is a bit much (as I'm sure it was intended to be), but it doesn't negate the hilarity of Bruno lurching, Kramer-like, head first into one metaphorical wall after another.

The opening minutes, in which Bruno throws a ripe-for-disruption fashion show into an uproar by wearing an all-velcro suit (and having a disastrous encounter with a curtain), are worth admission in themselves. I also particularly enjoyed the Paula Abdul segment (because of what she sits on) as well as the tableau of Bruno, ludicrously attired in African garb, removing from an airport baggage carousel a large tusk, an elephant foot, and a box marked "fragile" and containing a black baby. Everything is over-the-top, but that is Sacha Baron Cohen's shtick. The Ron Paul piece wasn't funny (he was one of the few unsuspected targets who acted with unsanctimonious dignity) and should have been cut, but overall Bruno wisely clocks in at (I'm guessing) 90 minutes or so. In an age when even good movies are too long (everything is getting quicker--except movies), this is a triumph in itself.

Bruno is not for the sexually squeamish, and its gay theme is no instance of social activism, but when it is funny, it is very funny indeed.

Monday, July 13, 2009

Rebooting Blues

Franz Marc, The Blue Fox

Franz Marc, The Blue FoxIs the blue fox anything like the black dog? As I get ready to close this blog (although not to delete it) and embark on a successor, I've been trying to arrive at a name that will be just right. I decided it ought to have "blue" in the title, for multiple reasons. It is a beloved hue, that of sea and sky, and it also denotes melancholia, which seems to me the paradigmatic mental disorder.

I love both the color and the word "ultramarine" ("beyond the sea"), but a long-dead blog already bears that title. Similarly "lapis lazuli," but that would be a bit baffling. "The Blue Book" or "The Blue Blog" would be nicely whimsical, but little more, and are probably already taken too. I considered "bolt from the blue," but it seemed trite; "the blue bulletin" seemed flat. "The blue bulb" carries the intriguing double meaning, both botanical and incandescent, but somehow didn't seem to flow.

So I thought about borrowing a blue phrase from Emily Dickinson, my poetic ideal. Her poems famously mention "my blue peninsula" as well as "a slash of blue," but believe it or not, now-expired blogs have used those titles also. Other instances include "breadths of blue," "withes of supple blue," and "inns of molten blue." Finally appeared the blue example that struck Goldilocks as being just right:

The Brain -- is wider than the Sky --

For -- put them side by side --

The one the other will contain

With ease -- and You -- beside --

The Brain is deeper than the sea --

For -- hold them -- Blue to Blue --

The one the other will absorb --

As Sponges -- Buckets -- do --

The Brain is just the weight of God --

For -- Heft them -- Pound for Pound --

And they will differ -- if they do --

As Syllable from Sound --

Blue to Blue--that's it, reflecting the refracting contributions of psychiatry and poetry, and without the stiff quasi-professional patina of Ars Psychiatrica. Blue to Blue juxtaposes brain and Earth, the vastness of the one rivaling the enormity of the other. Other areas of medicine deal merely with the humdrum body, while psychiatry confronts the universe of consciousness. "I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space, if it were not that I have bad dreams," Hamlet said. Poetry at its best acts as a rupture in reality, swinging open a portal onto the void.

As subtitle I'm thinking of "Psychology, Speculation, and Sea Change" (I'm a sucker for sibilants). According to Ariel:

Full fathom five thy father lies.

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes;

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

This summons another fascination, that of self-transformation, by self and of self by the sea of media and molecular influences we swim in. What about ourselves can be changed? How and how much? Should we change or merely accept?

The new blog's content will probably be similar to this, although with more emphasis on poetry (perhaps even--groan--some of my own). Under construction.

Addendum: Yes, others came to mind--"Blue Lagoon," "Baby Blue," "Blue Devil," and "Blue's Clues"--but, alas, all already used. "Cyanotic" might still be available, come to think of it.

Friday, July 10, 2009

Anniversary

The man-hero is not the exceptional monster,

But he that of repetition is most master.

Wallace Stevens

After 224 posts, Ars Psychiatrica is a year old--well, not quite, but in about three weeks, and as my kids would say, what's the harm in marking the occasion a bit early?

I undertook this blog after a relocation in which I chose to depart a tenured position in academia (after realizing that while in most of academia, tenure is life-saving, in medical academia it is merely an honorific). I had published a number of papers in obscure medical ethics and humanities venues, but felt like I still had things to say. I happened to find myself in a most peculiar job which had scandalous amounts of down time; for many months, most of the posts here were at least partially composed at work. Yes, it was a public job, so for quite a while this blog was taxpayer-funded; I am sorry, although it wasn't my fault (there really wasn't much else to do).

After a while I left that lame job behind and took on another one which, while involving fewer hours overall, kept me far busier while I was there. Due to that and other obligations, I found myself with less time to write, and probably I got lazy too, which is why in recent months illustrations and quotes petered out, and posts became less frequent. I noticed that readership went down: I think people really like cool pictures, although I wish content alone could carry the day.

The biggest challenge has been to define content and target audience: I have been torn between making professional issues at least the centerpiece of the blog on the one hand, and the inclination to give free rein to my eclectic instincts on the other. The latter has won out often enough that I'm sure that many people initially drawn to the blog in hopes of mainstream discussion of diagnosis and treatment were disappointed. I have found myself generally disinclined to write about work, narrowly construed. Shedding anonymity limited my openness as well.

Observing reading and commenting patterns has been fascinating. Some folks, to judge from both comments and Sitemeter data, come more or less to stay, while others, often after leaving comments suggesting the blog is the best thing since sliced bread, disappear, never to return. Was it something I said, or didn't say? Was s/he run over by a bus? I also think of Elaine's great Seinfeld line, and I paraphrase: "Is it possible that I'm not as attractive as I think I am?"

Timing and scheduling of posts remains tricky. Regularity and frequency help keep the blog's blood flowing, but a daily regimen can lead to some pretty perfunctory posts. Yet I dislike blogs where the author disappears for a few weeks every now and then with no explanation. Perhaps the best solution is scheduled posts a couple of times a week, such that folks know what to expect, yet one has time to work up something really worth posting. I'm curious too about all the abandoned blogs out there, which just stop without explanation: a dilapidated farmhouse in North Dakota, its occupants long gone for parts unguessed at.

I think blogging isn't done with me quite yet, but maybe it's time to overhaul the format, title, and theme. You know, go toe-to-toe with The Huffington Post. Mass appeal--MJ had it, why can't I? (Anonymous, don't answer that).

At the risk of being self-regarding (moi?), I thought I'd mention some of the posts during the year that I've enjoyed the most, usually because of the discussion they prompted. Some of this year's greatest hits: in one of my rare down-to-earth entries, You Be the Judge, folks helpfully advised me on a problem involving felines and unneighborly neighbors. A more highfalutin ethics discussion centered on capital punishment in Hippocrates and the Hangman.

I was tickled to get a surprise comment from the author himself after an appreciative review of Denis Dutton's The Art Instinct. While I enjoyed writing many of the literature entries most, they weren't the kind to generate a great deal of controversy or debate, but DFW Revisited attracted interest after Wallace's death last year. On a mainstream professional plane, posts on medication issues (On Med-Seeking and Old Wine, New Bottles) provoked not only lively comments but even a mention in the Los Angeles Times.

Easily my most controversial post, Uneasy Lies the Head, involved the political acceptability for high public office of those with major psychiatric diagnoses. I offered a heartfelt encomium of President Obama (The Case for Obama, Seriously) soon after his election last year (no, Retriever, I would not retract any of it today).

The question of proper compensation for psychiatrists attracted interest in How Much is a Psychiatrist Worth? The topic of the political persuasion of mental health professionals led to a rousing political tussle (I think Van der Leun has given up on me by now) in Where Liberals Lurk.

Finally, and more loftily, I and others considered spiritual issues in All in Your Head and The Missing All.

While I consider what to do now, I'll leave this post up for a while, so both panegyrics and take-downs are welcomed. Anyway, I figure the dog days start early here in the Carolinas...

Tuesday, July 7, 2009

Systole/Diastole

In the past couple of days The New York Times' Op-Ed section has featured two interestingly opposing views of the widely lambasted displays of Governors Mark Sanford and Sarah Palin. Stanley Fish, whose contrarian instincts were clearly at work here, argued that the emotional rawness exhibited by both figures should be honored as expressions of authenticity, and as refusals to play along with the artifice usually expected under the political microscope. In his view, the punditocracy viewed the two episodes with incomprehension precisely because they were not politically calculated. Omnia vincit amor.

David Brooks, while not condemning the two governors, saw their behavior as symptomatic of an age that has totally eschewed what used to be (at least in the days of the Founding Fathers, he suggested) a cultural ideal of decorum, dignity, and self-mastery. George Washington did not view his calm and relatively detached public face as some kind of mask--rather, it served the purpose of shaping (and not merely advertising) his moral and political conduct. The passions, whatever good they may do, are inherently potentially hazardous and must be curbed.

These positions more or less correspond to Romantic and Classical visions of the good life as consisting chiefly of feeling and order, respectively. I found myself agreeing with both of them, which suggests that the best life entails a balance of the two. Ages and cultures inevitably tilt more toward one or the other, and we have been in a Romantic age for quite a while now. The George Washingtons of the world just don't get the bloggers buzzing...

Is there some kind of parallel, even if not a simplistic one, between these two visions on the one hand and liberalism vs. conservatism on the other?

David Brooks, while not condemning the two governors, saw their behavior as symptomatic of an age that has totally eschewed what used to be (at least in the days of the Founding Fathers, he suggested) a cultural ideal of decorum, dignity, and self-mastery. George Washington did not view his calm and relatively detached public face as some kind of mask--rather, it served the purpose of shaping (and not merely advertising) his moral and political conduct. The passions, whatever good they may do, are inherently potentially hazardous and must be curbed.

These positions more or less correspond to Romantic and Classical visions of the good life as consisting chiefly of feeling and order, respectively. I found myself agreeing with both of them, which suggests that the best life entails a balance of the two. Ages and cultures inevitably tilt more toward one or the other, and we have been in a Romantic age for quite a while now. The George Washingtons of the world just don't get the bloggers buzzing...

Is there some kind of parallel, even if not a simplistic one, between these two visions on the one hand and liberalism vs. conservatism on the other?

Sunday, July 5, 2009

Mystics

In her commentary in The New York Times today Maureen Dowd describes the way in which people openly cite the criteria for Narcissistic Personality Disorder when speaking of Sarah Palin. I'm not supposed to go there, but it's interesting that even George Will sees her resignation as going nowhere in particular, and certainly not in the direction of eventual Presidential viability. Politics is hard, and not particularly glamorous unless one is very good at it indeed, and Palin seems to have seen an alternate route in rising above the fray, in wafting into an empyrean of Absolute Truth. She has a direct line.

At a birthday party I overheard my wife's uncle-by-marriage confiding his earnest hope that Obama will be assassinated. A democratically elected official, unless of course our count too was "rigged." What is one to say to that? To believe that one's interlocutors of the opposing party are beyond discussion, and can be meaningfully engaged only by annihiliation--is this not, really, fascism in the most general sense of the word?

Those with whom no dialogue is, in principle, possible can only be ignored and tolerated, eliminated, or perhaps enslaved. To face the incomprehensible Other, with whom no meaningful relation can be conceived, is an uncanny experience. Mysticism is always such a tempting option, but unfortunately it entails only a delicious feeling, and not reliable cognitive content; its mirror image is paranoia...

At a birthday party I overheard my wife's uncle-by-marriage confiding his earnest hope that Obama will be assassinated. A democratically elected official, unless of course our count too was "rigged." What is one to say to that? To believe that one's interlocutors of the opposing party are beyond discussion, and can be meaningfully engaged only by annihiliation--is this not, really, fascism in the most general sense of the word?

Those with whom no dialogue is, in principle, possible can only be ignored and tolerated, eliminated, or perhaps enslaved. To face the incomprehensible Other, with whom no meaningful relation can be conceived, is an uncanny experience. Mysticism is always such a tempting option, but unfortunately it entails only a delicious feeling, and not reliable cognitive content; its mirror image is paranoia...

Friday, July 3, 2009

Green Hell

What virtue resides in wildness? Through most of history wilderness was regarded as an evil, inimical to human prosperity. Only in the past century or two (since perhaps the Romantic movement and the Industrial Revolution, two sides of the same coin) has the developed world had the relative luxury of finding beauty in the untamed.

David Grann's The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon tells the story of Percy Harrison Fawcett, a hard-core British explorer who survived countless hazards until his luck finally ran out in 1925 (when his party vanished without trace deep in the jungle). Grann's fascinating account impresses upon us the fact that while we now see the Amazon as a fragile victim of heedless deforestation, as a quasi-Garden of Eden, the region in its original state was in fact an appalling nightmare for non-native human beings. It is hard to think of any area of the planet, polar regions and deserts included, whose climate, topography, fauna, and flora conspire more ferociously to the detriment of human welfare.

Therein resides its sublime attraction for some, I think--its very alienness, that is. Like an unbowed predator, the ocean depths, or the endless emptiness of space, it refuses to make room for us, enjoying instead its own inscrutable integrity. The glory of the Other exists not despite, but because, it can never fully be made hospitable.

Here is a sample of Grann's story (and you thought your summer camping trip went poorly):

Manley was the first stricken. His temperature rose to 104 degrees, and he shook uncontrollably--it was malaria. "This is too much for me," he muttered to Murray. "I can't manage it." Unable to stand, Manley lay on the muddy bank, trying to let the sun bake the fever out of him, though it did little good.

Next, Costin contracted espundia, an illness with even more frightening symptoms. Caused by a parasite transmitted by sand flies, it destroys the flesh around the mouth, nose, and limbs, as if the person were slowly dissolving. "It develops into...a mass of leprous corruption," Fawcett said. In rare instances, it leads to fatal secondary infections. In Costin's case, the disease eventually became so bad, as Nina Fawcett later informed the Royal Geographic Society, that he had "gone off his rocker."

Murray, meanwhile, seemed to be literally coming apart. One of his fingers grew inflamed after brushing against a poisonous plant. Then the nail slid off, as if someone had removed it with pliers. Then his right hand developed, as he put it, a "very sick, deep suppurating wound," which made it "agony" even to pitch his hammock. Then he was stricken with diarrhea. Then he woke up to find what looked like worms in his knee and arm. He peered closer. They were maggots growing inside him. He counted fifty in his elbow alone. "Very painful now and again when they move," Murray wrote.

Repulsed, he tried, despite Fawcett's warnings, to poison them. He put anything--nicotine, corrosive sublimate, permanganate of potash--inside the wounds and then attempted to pick the worms out with a needle or by squeezing the flesh around them. Some worms died from the poison and started to rot inside him. Others grew as long as an inch and occasionally poked out their heads from his body, like a periscope on a submarine. It was as if his body were being taken over by the kind of tiny creatures he had studied. His skin smelled putrid. His feet swelled. Was he getting elephantiasis, too? "The feet are too big for the boots," he wrote. "The skin is like pulp."

Only Fawcett seemed unmolested. He discovered one or two maggots beneath his skin--a species of botfly plants its eggs on a mosquito, which then deposits the hatched larvae on humans--but he did not poison them, and the wounds caused by their burrowing remained uninfected. Despite the party's weakened state, Fawcett and the men pressed on. At one point, a horrible cry rang out. According to Costin, a puma had pounced upon one of the dogs and was dragging it into the forest. "Being unarmed except for a machete, it was useless to follow," Costin wrote. Soon after, the other dog drowned.

It is a compelling read--mayhem recollected in tranquillity, and by proxy.

David Grann's The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon tells the story of Percy Harrison Fawcett, a hard-core British explorer who survived countless hazards until his luck finally ran out in 1925 (when his party vanished without trace deep in the jungle). Grann's fascinating account impresses upon us the fact that while we now see the Amazon as a fragile victim of heedless deforestation, as a quasi-Garden of Eden, the region in its original state was in fact an appalling nightmare for non-native human beings. It is hard to think of any area of the planet, polar regions and deserts included, whose climate, topography, fauna, and flora conspire more ferociously to the detriment of human welfare.

Therein resides its sublime attraction for some, I think--its very alienness, that is. Like an unbowed predator, the ocean depths, or the endless emptiness of space, it refuses to make room for us, enjoying instead its own inscrutable integrity. The glory of the Other exists not despite, but because, it can never fully be made hospitable.

Here is a sample of Grann's story (and you thought your summer camping trip went poorly):

Manley was the first stricken. His temperature rose to 104 degrees, and he shook uncontrollably--it was malaria. "This is too much for me," he muttered to Murray. "I can't manage it." Unable to stand, Manley lay on the muddy bank, trying to let the sun bake the fever out of him, though it did little good.

Next, Costin contracted espundia, an illness with even more frightening symptoms. Caused by a parasite transmitted by sand flies, it destroys the flesh around the mouth, nose, and limbs, as if the person were slowly dissolving. "It develops into...a mass of leprous corruption," Fawcett said. In rare instances, it leads to fatal secondary infections. In Costin's case, the disease eventually became so bad, as Nina Fawcett later informed the Royal Geographic Society, that he had "gone off his rocker."

Murray, meanwhile, seemed to be literally coming apart. One of his fingers grew inflamed after brushing against a poisonous plant. Then the nail slid off, as if someone had removed it with pliers. Then his right hand developed, as he put it, a "very sick, deep suppurating wound," which made it "agony" even to pitch his hammock. Then he was stricken with diarrhea. Then he woke up to find what looked like worms in his knee and arm. He peered closer. They were maggots growing inside him. He counted fifty in his elbow alone. "Very painful now and again when they move," Murray wrote.

Repulsed, he tried, despite Fawcett's warnings, to poison them. He put anything--nicotine, corrosive sublimate, permanganate of potash--inside the wounds and then attempted to pick the worms out with a needle or by squeezing the flesh around them. Some worms died from the poison and started to rot inside him. Others grew as long as an inch and occasionally poked out their heads from his body, like a periscope on a submarine. It was as if his body were being taken over by the kind of tiny creatures he had studied. His skin smelled putrid. His feet swelled. Was he getting elephantiasis, too? "The feet are too big for the boots," he wrote. "The skin is like pulp."

Only Fawcett seemed unmolested. He discovered one or two maggots beneath his skin--a species of botfly plants its eggs on a mosquito, which then deposits the hatched larvae on humans--but he did not poison them, and the wounds caused by their burrowing remained uninfected. Despite the party's weakened state, Fawcett and the men pressed on. At one point, a horrible cry rang out. According to Costin, a puma had pounced upon one of the dogs and was dragging it into the forest. "Being unarmed except for a machete, it was useless to follow," Costin wrote. Soon after, the other dog drowned.

It is a compelling read--mayhem recollected in tranquillity, and by proxy.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)