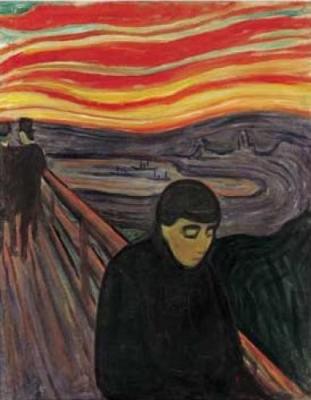

Macbeth: Cure her of that.

Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased,

Pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow,

Raze out the written troubles of the brain,

And with some sweet oblivious antidote

Cleanse the stuff'd bosom of that perilous stuff

Which weighs upon the heart?

Doctor: Therein the patient

Must minister to himself.

Macbeth: Throw physic to the dogs, I'll have none of it.

The other day I was reading an account of Mozart's final hours, in which he lay wracked by fever and pain, still idiopathic to this day. When the doctor arrived, he prescribed cold compresses. If that good medical man had any notion of what he was dealing with, what might it have been like to attend to one of the greatest composers in the history of the world and to be able to do nothing better than cold compresses? (Of course, it is thought that his life may have been iatrogenically shortened by previous blood-letting as well).

I've been reading Thomas Hines's Architecture of the Sun, a history of modernism in southern California, in which various people moved to that region upon medical recommendations of a more salubrious climate. Those were the days, when a prescription for sunlight, dry air, and palm trees was respectfully viewed as deep medical wisdom! A doctor's word could relocate people across continents.

The history of medicine is a weird amalgam of ignorance and authority, incapacity and power. Even through the millenia in which the practical (positive) effects of medicine were minimal, doctors nonetheless occupied a crucial social locus of judgment and prestige.

Physicians now fight for space in a more crowded arena, but some of their outsized influence remains. For better or worse, a diagnosis from a psychiatrist often carries more weight than one from a therapist. When patients need temporary time off from work or apply for disability, the paperwork seeks the opinion of the physician, not the therapist, nurse practitioner, or physician's assistant. The physician still wields the gavel of the sick role most vigorously.

But if, as the commenter to the previous post suggested, the primary function of the doctor must be the relief of suffering, what happens when the doctor's tools are in fact too weak to accomplish this, or what is more complicated, what happens when the effect of those tools is owing to their wielders' social power rather than to any inherent properties (i.e. the placebo effect)?

Much has been heard of late about the dubious effects of antidepressant drugs, an issue that can only give any psychiatrist serious pause. This issue has been raised many places, and this post is not intended as a literature review, but Sharon Begley's

Newsweek article may be as good a summary as any. If antidepressants are truly no better than placebo, then a scientific fraud on an unprecedented scale would have been perpetrated over the past half-century, and there would be something seriously rotten in the state of psychiatry.

I believe, of course, that antidepressants have real effects, otherwise I could not do my job in good faith. This belief could be deemed meaningless inasmuch as I have self-interested reasons of both professional standing and financial stability for holding it, and the human capacity for self-deception is unfortunately vast. But there are of course scientific reasons to doubt ambiguous drug trials, chief of which is the fact that many patients (or "patients") enrolled in drug studies are not representative of real clinical settings. Their disorders tend to be milder and more pure (i.e. uncomplicated by other diagnoses), and the very fact of their willingness to participate in a drug trial may heighten their response to placebo.

So, what do I believe about antidepressants based on 15 years of prescribing them to many hundreds if not a few thousand individuals in various settings? I believe that they are imperfect drugs that too often fail to work--my ECT experience alone would tell me that. I believe that antidepressants treat symptoms of still mysterious illnesses; they do not target the illnesses themselves. They are non-specific, affecting a broad spectrum of emotional response and anxiety level; in that sense they are more like what David Healy, in The Antidepressant Era, referred to as tonics than like magic bullets (think aspirin, not penicillin).

I believe that antidepressant effects are stronger, relative to placebo, the more severe and sustained depression or anxiety is. For mild and transient conditions they are often useless (thus the irony of the moral panic over Prozac-based emotional enhancement). I believe that people (prodded by drug advertising and cultural momentum) rely on them too much on average. Social and psychological interventions should be tried first.

But I refuse to believe, broadly and scientifically, that antidepressants are indistinguishable from placebos. For one thing, within the pharmacopeia there are a few drugs that I think of as internal placebos (buspirone or hydroxyzine, anyone?) having little effect beyond a hope and a prayer. But the mainstream antidepressants aren't like that, and while I know that the placebo effect is powerful and still not well understood, I have seen too many unimpressionable people with dramatic and sustained responses, and too many impressionable types who fail to improve, to believe that there is no physiological effect.

On what may seem like a trivial note, I haven't researched the literature, but many pet owners and veterinarians attest to the effects of Prozac, etc. on neurotic cats and dogs; can that merely be a mass phenomenon of placebo effect by proxy?